In 1855, future LDS Church President Joseph F. Smith, son of the martyr Hyrum Smith, was shipped off from Utah to the Sandwich Islands — now called Hawaii — to serve a three-year church mission. What makes it unique is that Smith was only 15. The mission call may have been an attempt to straighten out Joseph F., who had by many accounts a rough adolescence, particularly after his mother, Mary Smith, died when he was 13.

His missionary service served to mature the teen at an early age and he left his mission three years later a man both in size and spirit, with a dedication to the LDS Church that would never waver and lead him to becoming a prophet. The Smith-Petit Foundation, with editor Nathaniel R. Ricks, has compiled the surviving two years — 1856 and 1857 — of diary entries of his mission compiled by Smith. The first year’s entries were destroyed via a fire. They underscore the seriousness in which the teen took his mission, and the heavy responsibilities he was dealt while on the islands.

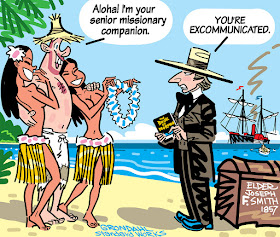

In fact, Smith was both a mission leader and ecclesiastical leader. In fact, he excommunicated members in the Sandwich Islands. Here’s an entry from April 18, 1856: “I attended meeting this morning and spoke some time to the Saints. Conference again convened at 10 o’clock, much business was transacted pertaining to the mission, among other things Charles S. Atkins was excommunicated from the church for stealing &c. a good spirit prevailed during the day.”

Just a few weeks earlier, Smith recounted a fight over scissors with another missionary that became violent. While working on garments, which in that era required certain parts to be sewed on, a Brother Gordon Linn accused Smith of stealing his scissors. After Linn called Smith a “Damn Shit ass,” Smith approached Linn, saying he wouldn’t take that, and was struck in the temple by Linn. Later in the diaries, there is correspondence between both missionaries that indicate the dispute was healed amicably.

Readers will also enjoy learning of the differences between missionaries of that era and today’s era. Although there were companions, it’s clear from the diaries that Smith was alone often. Also, he was encouraged at times to spend days away from proselyting. Many of the entries are of days spent reading novels, newspapers, letters or writing letters. He also hunted, sailed from Island to Island, milked cows, slaughtered turkeys and steers, worked as a carpenter, and went from house to house searching for food and provisions when supplies were low.

Smith was not immune from the frustrations that many missionaries — in a different culture — experience with the native people. He spent much of his mission trying to find enough food to eat, and was very harsh with the Sandwich Island people, who he thought hoarded food for themselves. The young missionary, although he expressed deep gratitude for helpful native members, was not immune from the bigotry of that era. No doubt meaning it well, Smith nevertheless promised native members in a March 30, 1856 sermon, saying “I spoke a short time by the spirit and prophysied that they would live (some of them) to see their children a white and delitesome people, if they would only obey the laws of God. ...”

Smith was scornful of missionaries from other faiths, as they no doubt were to him. Seeking salvation for the Sandwich Island dwellers was a competitive job among churches of that era. The teen although seethed in anger at apostate members, as well as apostate missionaries, who made his job much harder.

Despite the frankness of the diaries, it would be a help for today’s LDS missionaries to read Smith’s accounts. Many of his accounts include feelings and thoughts to missionaries of any era. The young Smith craved mail from home, and was disconsolate when it didn’t arrive as scheduled. He dealt with household pests (Nov. 6, 1856 entry reads in part: “… the objects of our Distress ware an innumirable quantity of domestic insects … called by some Fleas ...”), Illness, frequent homesickness, was frustrated with unmotivated church investigators and unhelpful local members. And, like many a missionary today, he romanced a girl from home with long letters that he eagerly awaited responses from.

Prior to Smith’s mission, earlier missionaries had enjoyed success in the area. However, time had eroded members’ enthusiasm and much of Smith’s work was devoted to reactivating branches and memberships. Many of the early members no longer considered themselves LDS and were excommunicated. Baptism totals during Smith’s tenure were low as the elders worked to repair the church’s foundation in that area. It’s clear that Smith was a highly valued missionary, willing to work hard and do tasks assigned to him. Readers of the diaries will enjoy even the most mundane entries, as they capture the stolid but diverse life of an early LDS Utah-based missionary.

Legend has it that Smith, upon returning to Utah after sailing to California from the Sandwich Islands, was accosted by a rough character asking if he was a Mormon. Smith, 18, is alleged to have replied, “Yes sir, dyed-in-the-wool, true-blue, through-and through!” After that response, the ruffian complimented Smith on his convictions. Whether the tale is true or not, there is no doubt that Smith’s teenage mission was instrumental in preparing him for a lifetime commitment to his religion.

-- Doug Gibson

-- Originally published at StandardBlogs