Thursday, April 25, 2019

David O. McKay diaries charts his life as a prophet

"Confidence Amid Change: The Presidential Diaries of David O McKay," (Signature Books, 2019), edited by scholar Harvard S. Heath, contains endearing examples of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' prophet. In one passage, McKay expresses how much he enjoyed an evening at the movies, watching "All About Eve." Throughout the diaries, McKay reveals his quiet pride in being treated graciously and with respect by U.S. presidents and other major political figures, notably presidents Dwight David Eisenhower and Lyndon Baines Johnson.

His personal emotions are revealed in diary entries. He hated the task of approving temple sealing cancellations. In another example, after what must have been a contentious meeting with his apostolic peers over a church personnel issue, McKay bristles that he had never been treated so harshly before in such a setting.

McKay served as LDS prophet from 1951 until his death in early 1970. His tenure was a bridge between Mormonism's foundation as a North American religion into its now global structure. A very conservative leader, fiercely anti-communist, McKay nevertheless served as a successful moderating influence to the political extremism of Apostle Ezra Taft Benson, who after serving as Agricultural Secretary to Eisenhower nursed national political ambitions. McKay also kept in check the ambitions of Brigham Young University, and church education leader, Ernest L. Wilkinson. A significant portion of the diaries include a long, back-and-forth saga over whether to retain then-named Ricks College in Rexburg, Idaho, or move it to Idaho Falls. McKay eventually chose to keep it in Rexburg, contrary to Wilkinson's wishes.

There are dozens of issues the diaries recall, often capturing the most private discussions in the highest councils of the LDS Church. They include concerns over the publication of Bruce R. McConkie's iconic "Mormon Doctrine," which McKay and others fretted contained more than 1,000 errors; quelling a fundamentalist rebellion among LDS missionaries in Europe; dealing with mismanagement; lobbying politicians on issues the church considered to be moral issues; trying to find a solution to several thousand black adherents in Nigeria who had already formed an unofficial church branch; dealing with Hollywood over a potential film adaptation of the Mountain Meadows Massacre; working with a financial expert -- successfully -- to improve the church's finances; debating the need for correlation in Sunday School and Priesthood lessons; planning the growth of temples, including some outside of the United States; and more.

We learn from the diaries the conversations McKay had with Utah leaders over policy, including the head of the Salt Lake City Chamber of Commerce and the publisher of the Salt Lake Tribune. With the Deseret News, McKay enjoyed considerable editorial power, and the diaries include one instance of his anger at a Deseret News editorial piece critical of Eisenhower that apparently slipped in without knowledge of higher ups at the paper. Another early incident in McKay's tenure was helping a U.S. congressman who had lied about his record arrange his resignation. He was deferred to by Utah's most senior politicians although his dealings with iconoclastic Utah pol J. Bracken Lee was more complex.

The diaries are excellent example of transparency that has been needed and -- in recent years -- of which we have seen a commendable increase of. Also captured are moments of unity and love expressed between the members of the First Presidency, Apostles, and others in the meetings. It's a reminder that despite the many debates, the group would function as supportive team once decisions were made. McKay, for most of his tenure, retained a strong independence, which weakened in his final years.

The diaries do no shirk from the racism of the period. While McKay was pragmatic on the black exclusion policy, allowing baptisms in cases where African lineage could not be conclusively proved, he did follow a cardinal policy at that time. It is distressing to read passages in which church leaders fret over Utah State University allowing black athletes, whom the leaders fear will date white young women, or read discussions to discourage the Armed Forces from moving African-American families to the Tooele area. The best that can be gleaned from this issue are indications from McKay, and others, that the policy would eventually be overturned via a revelation. In the diaries, it is sometimes justified using the context of the early apostles denying gentiles the opportunity to hear the Gospel, until the Lord determined otherwise.

Portions of the Heath-edited diaries include observations and notes from others, including McKay's longtime secretary Clare Middlemiss. Her entries become more poignant through the latter 1960s, as McKay's health slowly but consistently declines. One strength of the diaries is we experience the passage of a prophet's life. The initial burst of enthusiasm. The consistent energy of the leader's prime years, including highs and lows. We experience the personal strengths of his life, his relationship with his wife, Emma Ray, and the quiet fortitude his home in Huntsville often provided him. And we are witnesses to his decline, the more-frequent health problems and the longer periods of rest that are needed as his end nears.

These are poignantly captured, often by Middlemiss, with McKay's -- and occasionally his secretary's frustration -- with the prophet being excused from church duties by family members understandably concerned at the toll it was taking on his life. One of the more heart-rending accounts is very late in McKay's life when the prophet, with eyes closed, clutches his secretary Middlemiss' hand, saying he wants her with him. She recalls in the diaries that it would be the last time she was in his office.

Stephen L Richards, J. Rueben Clark, Benson, Harold B Lee, N. Eldon Tanner, Hugh B. Brown, Wilkinson, Alvin R. Dyer, a young Thomas S. Monson, all and many others occupy the diaries. I haven't done justice to how important this collection is to learn more about McKay's life, his role in the continuing evolution of the Latter-day Saints, and insights into how a church is governed. The best solution -- read it. The dead-tree book is expensive, but the Kindle version is an excellent buy at under $10.

-- Review by Doug Gibson

Saturday, April 20, 2019

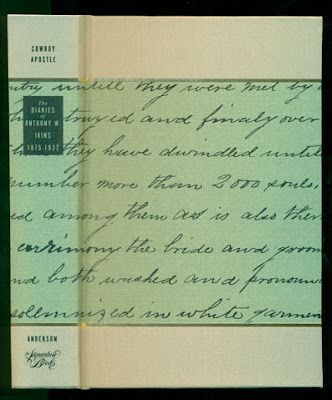

Diaries of the ‘cowboy apostle’ Ivins include secret Mormon plural marriages, political intrigue

On Sept. 12, 1932, Mormon apostle Anthony W. Ivins, first counselor to LDS President Heber J. Grant, made this diary entry. “On this date Prest. [Heber J.] Grant, who has been unwell for some time with prostrate gland trouble went to Chicago, for the purpose of undergoing an operation. He remained there for several weeks, during which time I was again alone in the office. [D]uring this time the October General Conference was held. I directed the [blank].” … According to editor, Elizabeth O. Anderson, Ivins stopped keeping a diary at this time, and died in 1934, at the then-very old age of 82.

Most of the entries in the latest Signature Books publication of early LDS leaders’ diaries are of the home, travel and work life “mundane.” Nevertheless, like other diaries, such as the 19th century Mormon apostle Abraham H. Cannon, “Cowboy Apostle: The Diaries of Anthony W. Ivins, 1875-1932,” it is fascinating reading for history buffs as well as scholars (Link). A day-to-day glimpse into the leaders who shaped the LDS Church in the first century of its existence. Ivins, called the “Cowboy Apostle” because he was an impressive physical specimen for most of his life, was a contrast to a typical LDS leader 100 to 120 years ago. He was a monogamist who was nevertheless sent to head the church’s Mexican mission, and conduct secret polygamous marriages years after the first Manifesto was issued. He was an active liberal Democrat who mulled a run for Utah governor and also clashed with another Mormon apostle/monogamist, Sen. Reed Smoot, a Republican.

Ivins arrived in Utah as an infant and his family settled in St. George. A cousin of Heber J. Grant, Ivins married a daughter of Mormon apostle Erastus Snow. In his early years, he was both a lawman and a district attorney in Southern Utah. He also helped on church exploration trips to Arizona and New Mexico.

There are a lot of “sexy” parts (think controversial) in the diaries, and I’ll get to some, but I prefer the “mundane” duties, the experiences, a mission president or apostle conducts during his life. Even today, the LDS Church hierarchy live lives cloistered even from the most active of members. That obscurity provides them a type of celebrity status in the church. Reading Ivins’ accounts of bargaining with a Mexican general to get land for suitable mission quarters, or taking in a “cockfight,” of all things, or resolving a dispute between two subordinates in the mission, or reading, “… went to Tecalco where we held meetings, I met a number of my old converts all of who I was glad to see & they seemed to reciprocate my feelings … (1902)” This is the wheat that provides nourishment for history to be recalled and taught.

As mentioned, Ivins was involved in expeditions as a young man, often under the supervision of his father in law, the apostle Erastus Snow. This entry from January 1878 is typical of Ivins’ life at the time: “This morning Bro. [Erastus] Snow started on with our team to camp at Navajo Springs and wait for us there. There being no forge at the ferry we could not weld the broken tire. We took a piece of heavy iron an[d] riveted it on the outside and I took the wheel back to bring up the wagons while Bro. Hatch made an axle for the one he had broken.”

Ivins witnessed the execution of John D. Lee for the massacre at Mountain Meadows. “… their guns resting on the spokes, the posse fired and Lee sank back upon the coffin, without a struggle, dead.”

A fascinating part of the diaries deals with an expedition, associated with Brigham Young Academy, to try to find Book of Mormon history. The late novelist Samuel Taylor has described this unsuccessful journey, but Ivins provides first-hand diary recollections, detailing the anguish some of the missionaries felt as the expedition stalled long before it could move beyond Mexico and into South America. As Ivins relates in his diaries from 1900, LDS President Lorenzo Snow and other church leaders urged the expedition leaders to disband and return, adding the promise that they would be honorably discharged from their “mission attempt.” The leader of the expedition, Brother Benjamin Cluff Jr., at one point, writes Ivins, “… said he greatly desired to go forward,” (adding) “… if he returned now the expedition would be a failure & his reputation was worth [more] to him than his life.” Ivins relates how church leadership gently tried to reassure Cluff and others that the mission could be ceased.

An interesting tidbit from the diaries is Ivins’ recording a speech from Church President Joseph F. Smith which specifically denounced the already-old “Adam-God” doctrine that Brigham Young had preached with enthusiasm. Ivins’ writes on April 8, 1912 “… Prest. [Charles W.] Penrose spoke on tithing. Adam God theory. Prest [Joseph F.] Smith. Adam God doctrine not a doctrine of the Church. …”

In the appendix of the diaries, there is a list of marriages that Ivins performed in Mexico, including many plural marriages after the First Manifesto. However, after the Second Manifesto, from President Joseph F. Smith at the time of Smoot’s efforts to become a U.S. senator, the ban on polygamy was finally taken seriously. Ivins’ diaries record the discussions between leadership in dealing with these post 1900 marriages. He writes in 1910, “... I have been in council with my quorum. … The question of plural marriages were discussed & it was decided that cases … where plural marriages were entered into prior to 1904 the parties to such marriages should not be molested unless they be cases where the interests of the church are involved. Where men are in prominence in the Church who have taken plural wives since Prest. [Wilford] Woodruff manifesto be removed where it can be done without giving unnecessary offence.” Prominent apostles disciplined for late plural marriages were John W. Taylor and Matthias Cowley.

Ivins lived a fascinating life; the diaries support that statement. Late in his life he disagreed with a statement that political rival Senator Smoot had done more for Mormonism than “all the missionaries,” countering that “he {Smoot] was not the only man in the church.”

These Signature diaries are very expensive but a treasures for those who love delving through history. Hopefully, they are in libraries for those with smaller wallets and purses to enjoy as well. (Another excellent review of this book is from Andrew Hamilton of the Association for Mormon Letters.)

-- Doug Gibson

-- Originally published at StandardBlogs

Wednesday, April 10, 2019

Isaac Russell, New York Times journalist, PR specialist for the Mormon Church

(Originally published at StandardBlogs in 2012)

At this year’s Mormon History Association conference in Calgary, two contributors, Michael Harold Paulos and Kenneth L. Cannon II, continued an annual practice of producing a keepsake booklet for attendees. This year’s booklet provided an abridgement of the Reed Smoot U.S. Senate hearings from Feb. 20, 1907, as well as a short feature on essays and correspondence provided by newspaperman Isaac Russell, both a Mormon and leading journalist in the first 20 years of the 20th century. In the booklet, the authors recount how Russell used his influence to recruit former President Theodore Roosevelt to harshly criticize a much publicized “magazine crusade” against the Mormon Church.

As the authors mention, Russell, whose jobs included a stint at the New York Times, was frustrated enough to write letters to magazines such as “Pearson’s,” “McClure’s,” and “Everybody’s,” who engaged in muckraking against the Mormons. In 1911, Russell, in what proved to be a brilliant public relations stroke, recruited the still very popular former President Theodore Roosevelt to criticize the muckrakers. In a long letter to Roosevelt, Russell claimed that the attacks against Mormonism in the magazines, which largely dealt with allegations of polygamy and theological power, originated from older stories, promoted by the anti-Mormon Salt Lake Tribune, which had circulated the accusations that Roosevelt — while president — backed Sen. Reed Smoot’s continued tenure in the Senate in exchange for the Mormons delivering the electoral votes of Utah, Idaho and Wyoming to Republicans in 1908.

Russell’s letter, carefully crafted, was designed to strike nerves within Roosevelt that were still boiling. The former president had always been angered by the allegations that he had bartered Smoot’s tenure for votes. For Roosevelt, Smoot not being a polygamist was enough for him to stay in the Senate. He was not convinced by charges from the Salt Lake Tribune and others that Smoot would be a puppet for Mormon President Joseph F. Smith while in the Senate.

To add pepper to Roosevelt’s anger, Russell reminded the former president that the current round of muckraking against Mormons in 1911 derived largely from charges made by Frank J. Cannon, who edited the Salt Lake Tribune when the corruption charges against Roosevelt were aired. At the time, Cannon, an excommunicated Mormon from a very prominent church family, was the leading critic of Utah, Joseph F. Smith and the Mormon Church. His series of charges in “Everybody’s” magazine would become a best-selling book and later he would make a fortune as a traveling anti-Mormon lecturer.

Roosevelt was no fan of Cannon, so placement of his name worked well for Russell’s purposes. The former president penned two letters to Russell. One was eventually published, as a letter to Russell, in “Collier’s Weekly” magazine, edited by Russell’s “good friend and sometimes-mentor, Norman Hapgood,” quotes the keepsake.

In the letter, Roosevelt, fervently and with outrage denies the accusations made in the muckraking pieces, calls the writers slanderers and also writes, “The accusation is not merely false, but so ludicrous that it is difficult to discuss it seriously. Of course, it is always possible to find creatures vile enough to make accusations of this kind. The important thing to remember is that the men who give currency to this charge, whether editors of magazines or the presidents of colleges, show themselves in their turn unfit for association with decent men when they secure the repetition and encouragement of such scandals, which they perfectly well know to be false.”

In an explanatory note after Roosevelt’s letter, Russell was able to get some digs in at the Salt Lake Tribune, which he accused of being run by a small group of persons feeding defamatory information about the Mormons to muckraking magazines across the country.

It was a brilliant feat of public relations produced by Russell, a very public limited approval of the Mormons by a popular former president and a public slap in the face to major magazines as well as to Cannon and other opponents of Russell’s church. As the authors of the keepsake write, it wasn’t all true. “Although Reed Smoot worried that Colonel Roosevelt would turn on the Mormons if he knew the truth about the continuation of polygamy, almost all other church leaders embraced” the Roosevelt letter.

The reaction from the muckrakers were less cordial. In Collier’s Weekly,” Harvey J. O’Higgins, who co-wrote Cannon’s anti-Mormon book, “Under the Prophet in Utah,” wrote a response to Roosevelt. It includes, “The machinery and discipline of the Mormon Church make the most perfect and autocratic church control of which we have any exact record. Because of this perfection of control, the new polygamy has been successfully hidden for these many years,” wrote O’Higgins.

With Roosevelt as an ally, however, Russell, and the Mormons had scored a battle victory over their adversaries. Church leaders were so pleased with Russell’s contacts and influence that he became, as the authors put it, a “secret press bureau” for the LDS Church in New York City, all while a full-time reporter for the New York Times. The keepsake provides examples of Russell’s Mormon press duties, including a couple of letters to his own newspaper, the Times, that he ghosted under the names of Eastern States LDS Mission presidents Ben E. Rich and Walter P. Monson.

In 1915, Russell received a personal letter from Joseph F. Smith, where the prophet tells Russell, “It is my sincere desire that you should continue as you are doing in defense of the truth and justice and the honor of your people, and always remember from whence you came while mingling with men who know not the truth but are given to following the customs and sins of the world.”

What a fascinating bit of history. Paulos and Cannon merit credit for bringing these candid tales, warts and all, of history, theology, journalism, spin and otherwise to interested readers.

The booklet keepsake, “Mormonism and the Politics of the Progressive Era,” is privately published by DMT Publishing, Salt Lake City. Copies are being provided to university libraries in Utah and other parts of the nation as well as to the LDS Church Historical Department.

--Doug Gibson

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)