A

friend loaned me a book published in 1956, "Saints

of Sage and Saddle: Folklore Among the Mormons," by Austin and Alta Fife, that

turned into a treasure over the weekend I read it.

"Saints of Sage..." is a collection of

Mormon folk tales and tall tales. Anecdotes abound from diverse sources that

include prophets and pioneers. The prologue essay, "A Mormon from the

Cradle to the Grave," is just plain outstanding. It's folksy and witty,

irreverent but never disrespectful. Latter-day Saints, warts and all, are

captured in this book, but there's always an affection underneath the banter.

I'd wager that any reader who has been a member

of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for at least 40 years can

recall hearing some of the folklore related in the book. One anecdote on

polygamy recalls two LDS apostles on the way to Idaho to attend a church meeting

passing a school with children tumbling out of the schoolhouse. A non-Mormon

reverend turned to the apostle and asked him if the scene reminded him of his

childhood. The apostle replied, "No, it reminds me of my father's

backyard."

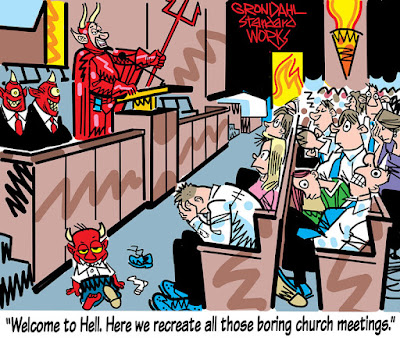

Long ago, when the church was more interesting

(as my friend Cal Grondahl says), devils were frequently cast out of hijacked

members and the Three Nephites tended not to be so publicity shy. In one

anecdote, one of the Nephite trio is generous enough to show himself to an elderly

lady who praised God that late in her life her prayer to see a Nephite perform

a miracle had been answered. LDS folklore has it that Governor

Thomas Ford of Illinois,

who failed to protect the Prophet Joseph Smith, died loathsome, unpopular and

in poverty. Another past anecdote involves LDS apostle and Logan Temple

president Marriner W. Merrill arguing with Satan himself in his temple office,

Old Scratch having visited to request that Merrill stop temple proceedings.

The LDS belief in a pre-existence is noted in

the book. Allegedly the LDS Prophet Wilford Woodruff warned in his journal that

there were literally trillions of Satan's army on earth doing their best to

lead them astray. Woodruff's calculation of the earth holding 1 trillion people

at a time seems way too high to this reviewer, though. Nevertheless, the Mormon

belief in a pre-mortal existence is very personal to members, who worry that

they may have lost friends and family members to Lucifer long ago. It can

provide mixed emotions on how to respond to temptation of a personal nature.

No book on Mormon folklore would be any good if

there wasn't a section on the legendary, cussing, LDS leader J. Golden

Kimball. He has a

chapter in "Saints of Sage ..." The former mule skinner once said,

"Yeah, I love all of God's children, but there's some of them that I love

a damn sight more than I do others."

Kimball also possessed wit: When former LDS U.S.

Sen. Reed Smoot wanted to marry, he boasted to Kimball that he had just

received the blessing of LDS Prophet Heber J. Grant. Kimball dead-panned,

"Well now, I just don't know, Reed. I just don't know. You're a pretty old

man, you know. And Sister Sheets, she's a pretty young woman. And she'll expect

more from you than just the laying on of hands."

And once, during an excommunication trial for a

man accused of adultery, Kimball, after hearing the man admit to being in bed

with the married woman but not having sex with her, laconically said,

"Brethren, I move that the brother be excommunicated. It's obvious that he

doesn't have the seed of Israel in him."

The Mountain Meadows Massacre, and its

aftermath, created much darker folklore. The wife of a Southern Utah Mormon, in

the brief interlude where the spared young children of the slain settlers were

being cared for in LDS homes, recalls a woman coming to her in her garden

asking to see her child. She was led into the house. The Mormon wife followed

the mysterious visitor, who disappeared the moment she reached the room where

the child was.

"Saints of Sage and Saddle" is

folklore history that the interested will spend hours poring over. Besides the

tales, there are old LDS hymns, period photos and an index for quick reference.

I choose to end this column with a song Mormons once enjoyed I encountered in

this book, and once sung by Ogden's

L.M. Hilton:

The Boozer

I was out upon a flicker and had had far too

much liquor,

And I must admit that I was quite pie-eyed,

And my legs began to stutter, and I lay down

in the gutter

And a pig arrived and lay down by my side.

As I lay there in the gutter with my heart

strings all aflutter,

A lady passed and this was heard to say,

You can tell a man who boozes by the company

he chooses.

And the pig got up and slowly walked away.

--Doug Gibson

Originally published

at StandardBlogs