--

This blog post was originally published in January 2011 on the now-defunct StandardBlogs. To my knowledge there are still many invested in the Dream Mine, although no work searching for riches goes on at the site. According to Wikipedia, there was an investors meeting in 2018.

One of the more fascinating nuggets in Utah Mormon history sits at the foot of a mountain in southern Utah County. Its official name is the Relief Mine, but most know of it as the “Dream Mine.” A long-used white mill building sits next to the mine, mostly inactive for decades. Nevertheless, the Relief Mine is a public company with assets of about $3.5 million. Stock in the mine is traded and there’s a waiting list to buy shares.

As Payson, Utah, writer/historian Kevin Cantera writes in the most recent Sunstone, “investors seeking to purchase a stake in the mine happily place their names on a waiting list for the chance to pay $30 to $35 for a single share — shares with a real value, by the most generous accounting, of less than $10 each.”

Cantera’s piece, “Fully Invested: Taking Stock in Utah County’s Dream Mine,” is as much a history lesson as it is a glimpse into the first 80 or so years of the LDS Church, where visions and prophecies from higher, celestial powers, whether from dad, your bishop or a general authority, were common. That’s a lost era. If a ward member gets up today and claims to have seen Christ or the Angel Moroni, we’re apt to trade concerned glances with our seat neighbors and look embarrassed. The bishop might call a regional rep if the claim is repeated. Can anyone imagine one of today’s apostles recounting experiences that early apostle Parley P. Pratt records in his diary?

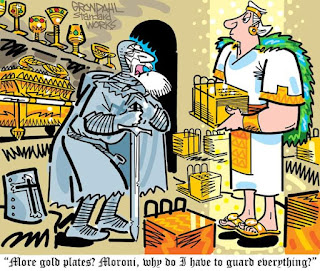

The shareholders in the Dream Mine are a throwback to the 19th century. They believe that deep into the Utah County mine there are piles and piles of gold and other precious artifacts, collected by the Nephites of Book of Mormon times. As Cantera recounts, some believe that perhaps the Sword of Laban, or even The Golden Plates, are hidden deep in the earth. The Relief Mine stockholders of the early 21st century aren’t looking for a return that will prompt a hefty capital gains tax. They expect their mine to pay off when the United States is on the brink of collapse and the dollar and other secular monetary systems have fallen.

The precious metals from the mine, and its relation to the Gospel, they believe, will save our nation from destruction in the last days. It’s an apocalyptic desire, one that was much more common 100-plus years ago, when a healthy percentage of blessings and priesthood ordinances promised the recipient that he or she would see the second coming of the Savior.

The prophet who launched the dream mine was Mormon bishop John Hyrum Koyle, who in 1894 claimed a nightime visit from the Angel Moroni, who showed him inside a mountain where there was a rich vein of gold. Lower down were nine caverns filled with Book of Mormon treasures, including the Urim and Thummim.

Koyle spent a long life preaching the doctrine of the Dream Mine and receiving revelations. He had some prominent LDS shareholders, including general authority J. Golden Kimball. The fact that there are still more than 1,000 faithful Latter-day Saints who believe Koyle’s claims underscores faithful Mormons’ strong belief of personal revelation from God. What was shouted from the pulpit long ago is regarded as best kept as a secret today, but there are enough apocalyptic Latter-day Saints out there to follow Koyle’s dream 117 years later.

And, although Koyle — after taking his spiritual mine public — was eventually repudiated by church leaders in 1913, and finally excommunicated in 1947, there are still mine stockholders, including Ogden’s Fred Naisbitt, who is quoted by Cantera as saying, “Koyle is second only to Joseph Smith in the number and accuracy of his prophecies.”

The white mill, which only gleaned 100 dollars worth of ore one year, still sits by the mountain near Spanish Fork, which draws more subdivision neighbors each year it seems. As Cantera reports, the Internet has strengthened the faith of the Dream Mine believers. The Web site is http://www.reliefmine.com but doresn't seem to work now. It had featured a glowing testimony of Koyle and links to other primitive LDS beliefs such as the White Horse Prophecy as well as notices that “the dollar will be utterly destroyed.” There is a Facebook page with contact information.

Who knows? Maybe the dollar will be destroyed. But to most Mormons, even in Utah County, the longer odds are on the Dream Mine one day paying off.

-- Doug Gibson